Project

Interrogating the role of hydrolases on colonic barrier dysfunction

| Primary Investigator: | Dr Rachael Barry Imperial College London |

| Funder: | Emulate/Organ-on-a-chip Network Proof-of-concept Award |

| Project dates: | 29-10-2020 to 29-10-2021 |

| Centre dates: | 08-04-2021 to 07-10-2021 |

Every year over 16,000 people die due to colon cancer in the UK and with an increasingly aged and obese population this number is increasing (2015-2017; Cancer Research UK/CRUK). Ninety percent of people diagnosed with colon cancer will survive if detected and treated early (Bowel Cancer UK). To do this, improved biological markers for early diagnosis and novel treatment methods are urgently needed.

Proteins that disrupt colon function are ideal candidates as drug targets and early markers of disease. The colon is part of our gut and one of its key functions is to provide a barrier between our immune system and the 100 trillion microbial organisms that live in your gut. Damage to the colon barrier exposes our immune system to the gut microbes, which reacts by mounting an immune response. If the damage is not fixed, the constant immune response drives more damage that leads to diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer.

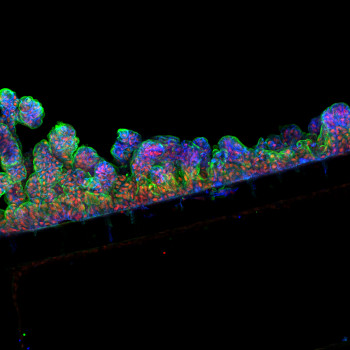

In the gut, proteins called hydrolases are vital for human health. These hydrolases work by breaking down other molecules. In a healthy gut, hydrolases include digestive enzymes such as trypsin and enzymes from gut microbes. However, in a damaged gut, immune cells are a major source. An uncontrolled immune response results in too much hydrolase activity which destroys tissues. I have recently shown that one hydrolase released from white blood cells of the immune system is present in faeces and contributes to damage in the colon in people with inflammatory bowel disease. Thus, I want to test if additional hydrolases from a colon harbouring a strong immune response (like in inflammatory bowel disease or cancer) damage the colon barrier and are thus drivers of colon cancer development. To test this, I will; i) establish cutting-edge gut culture models known as colon-on-a-chip, ii) add faecal liquid from people with colon cancer or healthy individuals and measure colon barrier damage, iii) rescue barrier damage by adding commercial or custom-made hydrolase blocking drugs.

This pilot project will lead to an established colon-culture model to generate proof of concept data that hydrolases damage the gut barrier, to what degree, and that drugs blocking hydrolase activity can prevent this. The next step will be to obtain funding to identify these hydrolases and generate more specific inhibitors. This second step will be in collaboration with Prof. Ed Tate a world-leading chemical biologist. Pinpointing hydrolases that contribute to colon barrier dysfunction will provide key knowledge about drivers of colon cancer. As hydrolases are active proteins blocking their activity offers new future treatment options for colorectal cancer with the goal to save lives.